Bonding Over Bans: Strengthening the US-Japan Tech Alliance Amid China’s Influence

Click here to view and download this article as a printable pdf.

Ian Wong (Nagasaki, 2022-2023)

On April 27, 2023, U.S. National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan gave a speech at the Brookings Institution where he identified two crucial issues facing the United States: the hollowing out of America’s industrial base and intensifying competition with China. These challenges, Sullivan argued, called for a rethinking of U.S. domestic and foreign policy. (1) What exactly did Sullivan mean?

Over the course of 2023–2024, the U.S. government has rolled out a “small yard and high fence” policy that seeks to strengthen the advantages America holds in foundational technologies. Crucially, this policy has also been designed to prevent its key geopolitical rival, China, from accessing cutting-edge semiconductor technology—exemplifying how U.S. officials believe that chips will be the biggest drivers of the future economy. Yet this small yard of restricted technology requires American allies’ buy-in to construct a high fence. To that end, the United States has worked with its allies to construct a web of export controls such that China cannot buy advanced chips through side channels. Chief among these allies has been Japan, another crucial player in the semiconductor industry. Together, the two aligned nations have sought to hamper China’s research and development on multiple occasions through what can be called “cooperative prohibition.” Yet cooperative prohibition is not without its limits.

Two case studies involving such restrictions—one on Chinese telecommunications company Huawei and another on advanced semiconductors—show the subtle yet distinct differences between how the United States and Japan have constructed their controls and illustrate how Japan has sought to hedge between the world’s two superpowers. China has sought to exploit these cleavages to its advantage, pushing for a stronger relationship with Japan. The United States must not be complacent in this trilateral dynamic. While the United States and Japan are close allies, full alignment on the two countries’ China policy should not be taken as a given. Instead, the United States should deepen its technological cooperation with Japan, providing incentives for the country to continue working with them on issues of mutual interest.

U.S. Technology Controls

The United States has made no attempts to conceal its approach towards China. In multiple speeches, U.S. officials have stated that the two countries are “in competition.” (2) They regularly point to differences in each country’s values and argue that China has built an unfair advantage by heavily subsidizing its domestic companies. In the case of technology, the United States has voiced fears that Chinese technology could collect American’s personal information, or conversely, that U.S. technology used in appliances abroad may end up in the hands of the Chinese military.

As such, the technology restrictions that the United States has placed on China are largely framed through the lens of national security. Take the restrictions on Huawei as an example. In December 2017, the Trump administration barred the U.S. Department of Defense from procuring telecommunications equipment from Huawei if such machinery were a “substantial or essential component” of technology used for nuclear deterrence or homeland defense missions. (3) This directive was broadened in August 2019, whereby all executive branches were expected to cut Huawei out of their technological systems. Finally, in May 2019, the U.S. Department of Commerce added Huawei to the “Entity List,” thus compelling Huawei to receive U.S. government approval to buy American technology. (4) This action effectively barred Huawei from purchasing U.S.-made microchips and other technology important to the company’s operations.

This story is similar to the one on semiconductor export controls. In October 2022, the U.S. Department of Commerce called China out by name, stating that its new regulations aimed to restrict China’s “ability to obtain advanced computing chips…and manufacture advanced semiconductors” in order to protect “U.S. national security and foreign policy interests.” (5) These rules were tightened a year later, rounding out a cascade of technology restrictions aimed at China. (6)

The success of these controls has hinged on the United States’ ability to convince its allies to adopt parallel rules. Indeed, if other countries do not institute similarly strict export controls, China can simply bypass the United States and deal with third-country suppliers willing to sell them advanced chips. In response to these concerns, the United States has held multiple rounds of negotiations with its allies, chief among them Japan and the Netherlands. Its work thus far has yielded results. After meetings between the three countries (7) in January 2023, both Japan and the Netherlands agreed in practice to restrict exports of advanced chip-manufacturing equipment to China. This case captures the dynamics of cooperative prohibition. To be sure, most technology cooperation is decidedly knowledge-producing. For instance, the United States and Japan agreed in 2022 to collectively boost semiconductor research and development as well as strengthen supply chain resiliency between themselves and other “like-minded countries across the region.” (8) Yet this emphasis on shared values goes both ways as the case of technology controls on China illustrates. Faced with a state that defies the “rules-based order” espoused by those in Washington, DC, the United States has rallied its partners towards a different form of technological cooperation—one characterized not by knowledge production amongst allies, but of knowledge prohibition against competitors.

Achieving cooperative prohibition is no simple task, however. Semiconductor firms in the United States, Japan, and the Netherlands operate in different parts of the semiconductor ecosystems. In addition, the three countries confront different geopolitical considerations in their respective relations with China. This is especially the case for Japan, which has substantial business interests in its neighboring country, not to mention a complicated historical relationship with it as well.

Cooperating and Hedging: Japan’s Strategy

On the surface, Japan has broadly followed the lead of the United States when it comes to technology controls. In December 2018, the Japanese government effectively banned its central government ministries and the Self-Defense Forces from buying personal computers, servers, and telecommunications equipment manufactured by Huawei. (9) In March 2023, Japan once again announced technology restrictions, stating that it would implement controls on twenty-three types of advanced semiconductor manufacturing equipment starting July 2023. (10) In both the case of Huawei and semiconductors, Japan’s technology measures came just after the United States had announced its own. Japan’s justification also followed U.S. rationale: protecting national security and preventing leaks of sensitive information. One would be mistaken, however, in believing that Japan was blindly following U.S. policy letter for letter.

In contrast to pointed comments by the U.S. government, conspicuously missing from each iteration of Japanese technology control is any mention of China. When questioned about the “Huawei ban,” then-Prime Minister Shinzo Abe emphasized that the new rules were “not intended to exclude any particular company or device” from the procurement process. (11) This approach remained the same for semiconductors. In a 2023 press conference immediately following Japan’s promulgation of chip curbs, Minister of Economy, Trade, and Industry Yasutoshi Nishimura stated that the trade restrictions were “not designed with a specific country in mind.” He went a step further, stressing that “we are not following the United States in any way.” (12) Though aligning its policy with that of its ally the United States and taking action with China in mind, Japan has rhetorically denied any concrete geopolitical considerations in the targeting of its new rules. These seemingly contradictory positions represent a delicate balancing act that Japan seeks to pull off, hedging between its close partner on one hand while working to steady relations with its powerful neighbor on the other.

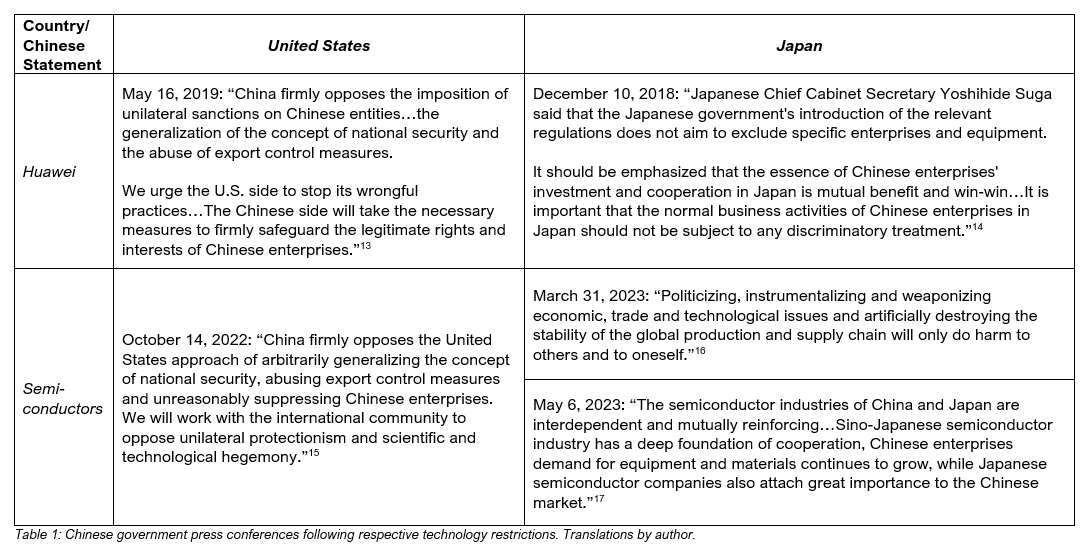

China has responded positively to these rhetorical overtures, at least when compared to its reaction to American actions. Table 1 shows the different responses the Chinese government offered when the United States and Japan imposed their respective technological restrictions on Huawei and advanced semiconductors.

Clearly, China softened its discourse when addressing Japanese technology restrictions. In its official statements, the Chinese government chose to both acknowledge Japan’s decision to institute country-agnostic policies and to leave the door open for future China-Japan engagement by highlighting the “win-win” nature of cooperation between the two nations. This gentler response is in stark contrast with China’s sharp critique of the United States’ “unilateral protectionism” and “abuse of export control measures.” Taken together, a picture emerges of Japan seeking to hedge between its ally across the Pacific and its Asian neighbor and China trying to capitalize on Japan’s juggling act to incentivize Chinese-friendly behavior.

China’s strategy is starting to make inroads with Japan. In Japan’s Diplomatic Bluebook 2024, the country’s annual report on Japanese foreign policy, the country described its ties with China as “mutually beneficial strategic relations” (senryaku-teki gokei kankei)—the first time the term has appeared in the report since 2019. (18) This was no coincidence. In November 2023, President Xi Jinping met with Prime Minister Kishida on the sidelines of the Asia-Pacific Economic Cooperation meetings where both sides agreed to revive the positive characterization of Sino-Japanese relationships. (19) As the U.S. presidential election draws near, there has been a noticeable uptick in high-level Sino-Japanese engagement beyond leader-to-leader meetings. In July, Chinese Foreign Minister Wang Yi met his Japanese counterpart Yoko Kamikawa for the first one-on-one meeting in eight months. (20) The week prior, foreign affair officials from both countries held a strategic dialogue, reviving talks that had been dormant for four years. (21) The two countries are continuing to stabilize ties as their ally and competitor, respectively, faces an uncertain political future.

Paths Forward

To be sure, the United States is a clear ally with Japan while the same cannot be said for China. The latter two countries share a complex relationship, especially given the painful memories from World War II. Two recent incidents showcase how historical legacies remain achingly present in contemporary society: the attempt to stab a Japanese mother and child outside of a Japanese school in China (22) and the defacing of the Yasukuni Shrine in Tokyo by a Chinese man to protest Japan’s release of the Fukushima wastewater. (23) However, these discontents simmering in the Sino-Japanese relationship do not automatically ensure seamless U.S.-Japan relations, especially in light of the Chinese government’s attempts to draw Japan closer to its side.

To best set up U.S.-Japan cooperation moving forward, the United States must provide assurances that its commitment to an alliance with Japan is steadfast. Indeed, a key obstacle to the two countries’ upgrading of military ties in July was reportedly Japanese officials’ concerns if such an upgrade would endure beyond the upcoming U.S. presidential election. (24) Regardless of which party wins control of the White House, the newly inaugurated president should put reaching out to the Japanese government as one of their top priorities. This gesture could include making a U.S.-Japan leaders meeting a priority soon after taking office and committing to an expedient renegotiation of the Status of Forces Agreement for U.S. forces based in Japan—an agreement set to expire in 2026. These steps would project stability on the American side, showcasing a commitment to maintaining strong ties between the two allies.

Moreover, the new administration would be well served to encourage deeper technological cooperation between companies on both sides of the Pacific. A good model for such cooperation would be the IBM-Rapidus partnership to jointly develop advanced semiconductors. While such technology will be produced in fabrication plants by Rapidus in Japan, research is being conducted in the United States at the Albany NanoTech Complex—a leading semiconductor research facility. (25) In this way, U.S. and Japanese firms can build enduring partnerships while also further integrating Japan into a global supply chain of semiconductors built by like-minded states and businesses. A key reason China has made progress in its relationship with Japan has understandably been Japan’s reluctance to alienate a large market next door without clear reassurances that U.S.-Japan technological cooperation would prevail. Taking these two steps would go a long way in assuaging these concerns while bolstering the U.S.-Japan alliance.

Strengthening the U.S.-Japan relationship will be crucial for future endeavors, and it would be a mistake to take broad alignment as a foregone conclusion. The Biden administration once again reached out to Japan this July over cooperative prohibition measures, mulling over rules to penalize companies that sell products to China with even the smallest amount of U.S. technology. (26) As these negotiations kick into high gear against the backdrop of rising geopolitical tensions, the United States would do well communicating with one of its foremost partners. Continuous engagement on both sides will be a prerequisite for the two allies as they navigate an increasingly polarized world.

About the Author

Ian Wong taught on the JET Program from 2022-2023 in Nagasaki Prefecture. He is a Yenching Scholar at Peking University in Beijing. Studying politics and international relations, Ian’s research interests lie in U.S.-Japan-China relations and subnational ties. Ian is currently working at Trivium China covering geopolitics in the East Asia region. Previously, he worked at global consulting firm Albright Stonebridge Group, and the American Chamber of Commerce in Hong Kong. His publications have appeared in Princeton Journal of East Asian Studies and Chicago Journal of Foreign Policy. He graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of California, Berkeley. Splitting his childhood between Boston and Hong Kong, Ian is a proud Red Sox fan and lover of diner-style cha chaan tengs.

References

(1) Jake Sullivan, “Remarks by National Security Advisor Jake Sullivan on Renewing American Economic Leadership at the Brookings Institution” (speech delivered at The White House, April 27, 2023, https://www.whitehouse.gov/briefing-room/speeches-remarks/2023/04/27/remarks-by-national-security-advisor-jake-sullivan-on-renewing-american-economic-leadership-at-the-brookings-institution/).

(2) Daniel Kritenbrink, “U.S.-China Relations,” United States Department of State (blog), February 22, 2023, https://www.state.gov/briefings-foreign-press-centers/us-china-relations/.

(3) Stephen P. Mulligan and Chris D. Linebaugh, Huawei and U.S. Law, Congressional Research Service, February 23, 2021, https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R46693.

(4) Alexandra Alper, “U.S. Actions against China’s Huawei,” Reuters, November 2021, https://www.reuters.com/graphics/USA-CHINA/HUAWEI-TIMELINE/zgvomxwlgvd/.

(5) Bureau of Industry and Security, “Commerce Implements New Export Controls on Advanced Computing and Semiconductor Manufacturing Items to the People’s Republic of China (PRC),” U.S. Department of Commerce, October 7, 2022, https://www.bis.doc.gov/index.php/documents/about-bis/newsroom/press-releases/3158-2022-10-07-bis-press-release-advanced-computing-and-semiconductor-manufacturing-controls-final/file.

(6) Emily Benson, “Updated October 7 Semiconductor Export Controls,” Center for Strategic and International Studies, October 18, 2023, https://www.csis.org/analysis/updated-october-7-semiconductor-export-controls.

(7) Jing Zhang et al., “Japan and the Netherlands Agree to New Restrictions on Exports of Chip-Making Equipment to China,” Mayer Brown, February 28, 2023, https://www.mayerbrown.com/en/insights/publications/2023/02/japan-and-the-netherlands-agree-to-new-restrictions-on-exports-of-chipmaking-equipment-to-china.

(8) U.S. Department of Commerce, “First Ministerial Meeting Japan U.S. Commercial and Industrial Partnership,” fact sheet, May 4, 2022, https://www.commerce.gov/sites/default/files/2022-05/First%20Ministerial%20Meeting%20Japan%20US%20Commercial%20and%20Industrial%20Partnership.pdf/.

(9) “Japan Bans Huawei and Its Chinese Peers from Government Contracts,” Nikkei Asia, December 10, 2018, https://asia.nikkei.com/Economy/Trade-war/Japan-bans-Huawei-and-its-Chinese-peers-from-government-contracts.

(10) Tim Kelly and Miho Uranaka, “Japan Restricts Chipmaking Equipment Exports as It Aligns with U.S. China Curbs,” Reuters, March 31, 2023, https://www.reuters.com/technology/japan-restrict-chipmaking-equipment-exports-aligning-it-with-us-china-curbs-2023-03-31.

(11) Prime Minister’s Office of Japan, “Press Conference by Prime Minister Shinzo Abe on December 10, 2018” [in Japanese], press release, December 10, 2018, https://www.kantei.go.jp/jp/98_abe/statement/2018/1210kaiken.html.

(12) Ministry of Economy, Trade and Industry, “Summary of the Press Conference by Minister Nishimura after the Cabinet Meeting” [in Japanese], April 4, 2023, https://www.meti.go.jp/speeches/kaiken/2023/20230404001.html.

(13) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lu Kang’s Regular Press Conference on May 16, 2019” [in Chinese], May 16, 2019, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/wjb_673085/zzjg_673183/gjs_673893/gjzz_673897/lhgyffz_673913/fyrth_673921/201905/t20190516_7657494.shtml.

(14) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Lu Kang’s Regular Press Conference on December 10, 2018” [in Chinese], December 10, 2018, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/web/wjdt_674879/fyrbt_674889/201812/t20181210_7814215.shtml.

(15) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Mao Ning’s Regular Press Conference on October 14, 2022” [in Chinese], October 14, 2022, http://newyork.china-consulate.gov.cn/chn/fyrth/202210/t20221014_10783635.htm.

(16) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, “Foreign Ministry Spokesperson Mao Ning’s Regular Press Conference on March 31, 2023” [in Chinese], March 31, 2023, https://www.mfa.gov.cn/fyrbt_673021/jzhsl_673025/202303/t20230331_11052523.shtml.

(17) Ministry of Commerce of the People’s Republic of China, “The China Semiconductor Industry Association’s Statement on Japan’s Proposed Semiconductor Export Control Measures” [in Chinese], May 6, 2023, http://exportcontrol.mofcom.gov.cn/article/gndt/202305/815.html.

(18) Ministry of Foreign Affairs of Japan, Diplomatic Bluebook 2024 [in Japanese], https://www.mofa.go.jp/mofaj/files/100653233.pdf; Zeyu Yao, “Why Does Japan’s Positioning toward China Fluctuate between ‘Strategic Reciprocity’ and ‘Strategic Challenge’?” [in Chinese], China Institute of International Studies, April 24, 2024, https://www.ciis.org.cn/yjcg/sspl/202404/t20240424_9241.html.

(19) Bajiang Yang and Sichun Chang, “China and Japan Reaffirm Their Strategic and Mutually Beneficial Relationship” [in Chinese], People’s Daily, November 23, 2023, http://paper.people.com.cn/rmrb/html/2023-11/23/nw.D110000renmrb_20231123_2-17.htm.

(20) Bernard Orr and John Geddie, “China Says Relations with Japan at ‘Critical Stage,’” Reuters, July 26, 2024, https://www.reuters.com/world/asia-pacific/chinese-foreign-minister-says-relations-with-japan-critical-stage-2024-07-26/.

(21) Shimpei Kawakami, “Japan and China Resume Strategic Dialogue after 4 Years,” Nikkei Asia, July 23, 2024, https://asia.nikkei.com/Politics/International-relations/Japan-and-China-resume-strategic-dialogue-after-4-years.

(22) Ken Moritsugu, “Knife Attack at a School Bus Stop in China Wounds 3, Including a Japanese Mother and Child,” AP News, June 25, 2024, https://apnews.com/article/china-japan-knife-attack-stabbing-school-child-875b7f113b52a71113fa60686c6530e2.

(23) Yvette Tan, “Chinese Man Arrested after Japanese Yasukuni Shrine Vandalised,” BBC News, July 9, 2024, https://www.bbc.com/news/articles/cv2g5nz00vko.

(24) Stuart Lau, “U.S. Revamps Japan Command amid China’s Threats,” Politico, July 28, 2024, https://www.politico.eu/article/us-revamps-japan-command-amid-chinas-threats/.

(25) IBM Newsroom, “Rapidus and IBM Expand Collaboration to Chiplet Packaging Technology for 2nm-Generation Semiconductors,” news release, June 3, 2024, https://newsroom.ibm.com/2024-06-03-Rapidus-and-IBM-Expand-Collaboration-to-Chiplet-Packaging-Technology-for-2nm-Generation-Semiconductors.

(26) Mackenzie Hawkins et al., “U.S. Floats Tougher Trade Rules to Rein In China Chip Industry,” Bloomberg.com, July 17, 2024, https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2024-07-17/us-considers-tougher-trade-rules-against-companies-in-chip-crackdown-on-china.

JETs on Japan is a partnership between USJETAA and Sasakawa Peace Foundation USA (Sasakawa USA) that features selected articles of JET alumni perspectives on US-Japan relations. The series aims to elevate the awareness and visibility of JET alumni working across diverse sectors and provides a platform for JET alumni to contribute to a deeper understanding of US-Japan relations from their fields. The articles will be posted on USJETAA’s website to serve as a resource to the wider JET alumni and US-Japan communities on how alumni of this exchange program are continuing to serve as informal ambassadors in US-Japan relations.

Submissions are encouraged from mid-to-senior level professionals who are established in the current fields OR current/recent graduate degree students in both master’s and doctoral programs.